Locations,

way of life, society

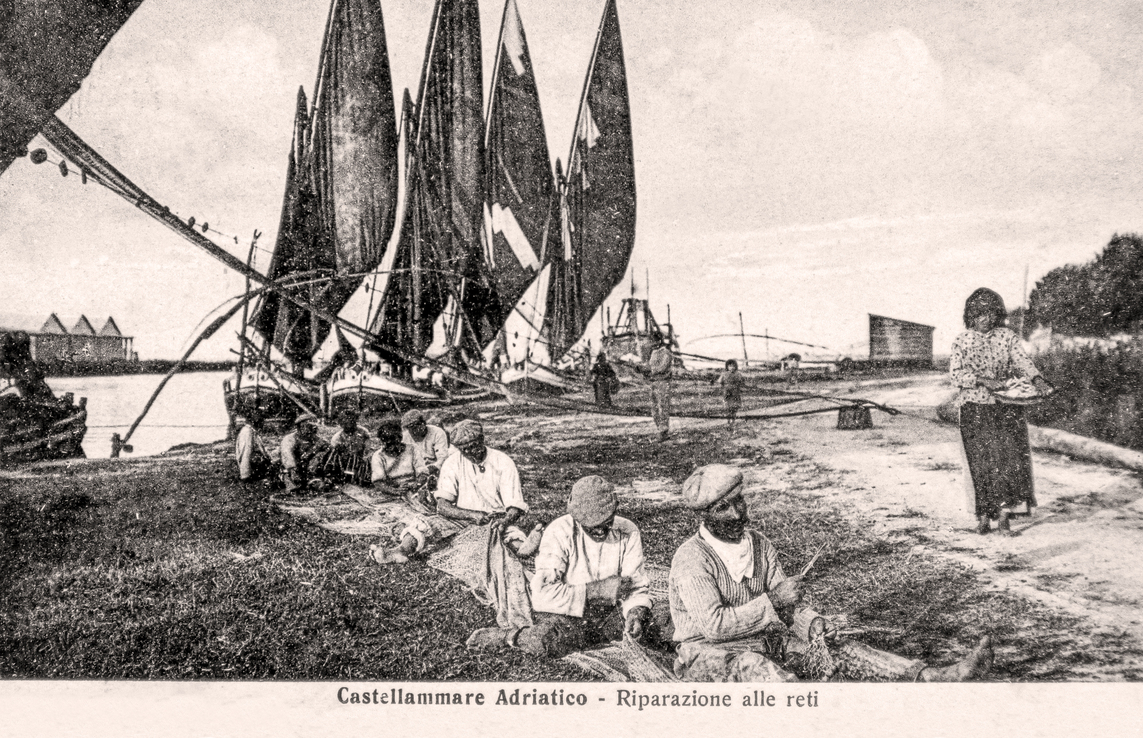

their districts were isolated and they lived in shacks, built spontaneously one next to the other, near their storage rooms and chaotic outdoor work spaces, their lives conducted mainly out in the open. The dominant intermarriage system exacerbated both the cultural and physical isolation of these communities, although it was open to the arrival and integration of new fishing family groups, like a number of Veneto groups from Chioggia and Caorle, who reached the Abruzzo coast at the end of the 1600s, or other large groups migrating from the Marche region in the latter half of the 1800s.

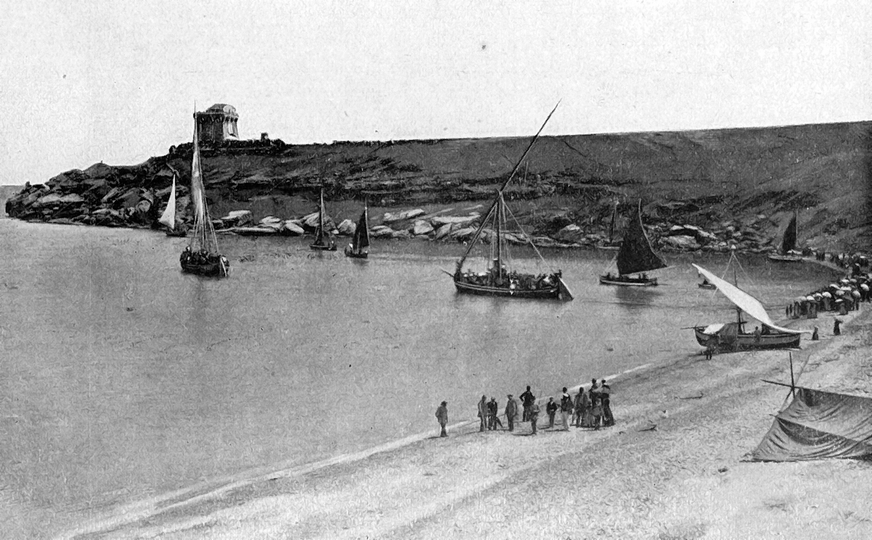

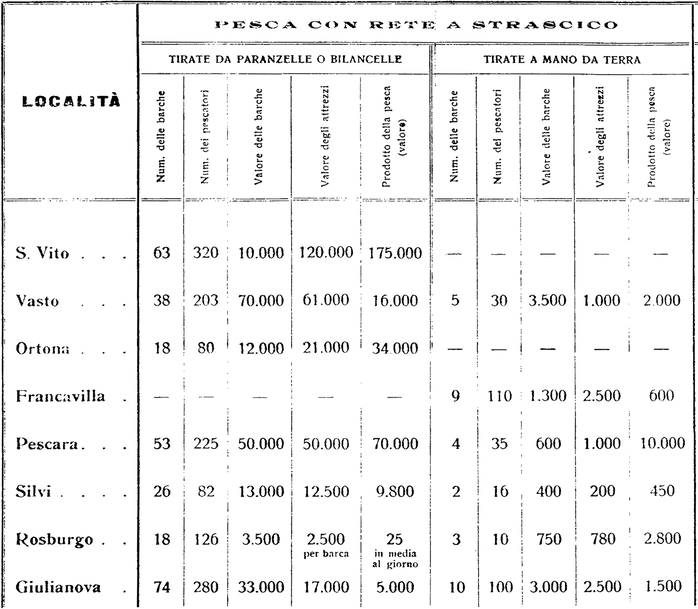

At time of the outbreak of the First World War, 3,772 fishermen were recorded in the seafarers registers for the maritime district of Ortona, which included the ports of Termoli, Vasto, San Vito, Francavilla, Pescara, Rosburgo (Roseto) and Giulianova. Then there were 377 fishing boats, of which 200 registered in the larger ports of Ortona and Pescara.

Gathered in small communities overlooking the sea and close to their means of sustenance, fishing families developed cultural diversity over time, dictated by the unstable coastal climate and the seasons, which changed their way and pace of life, both at work and at home;

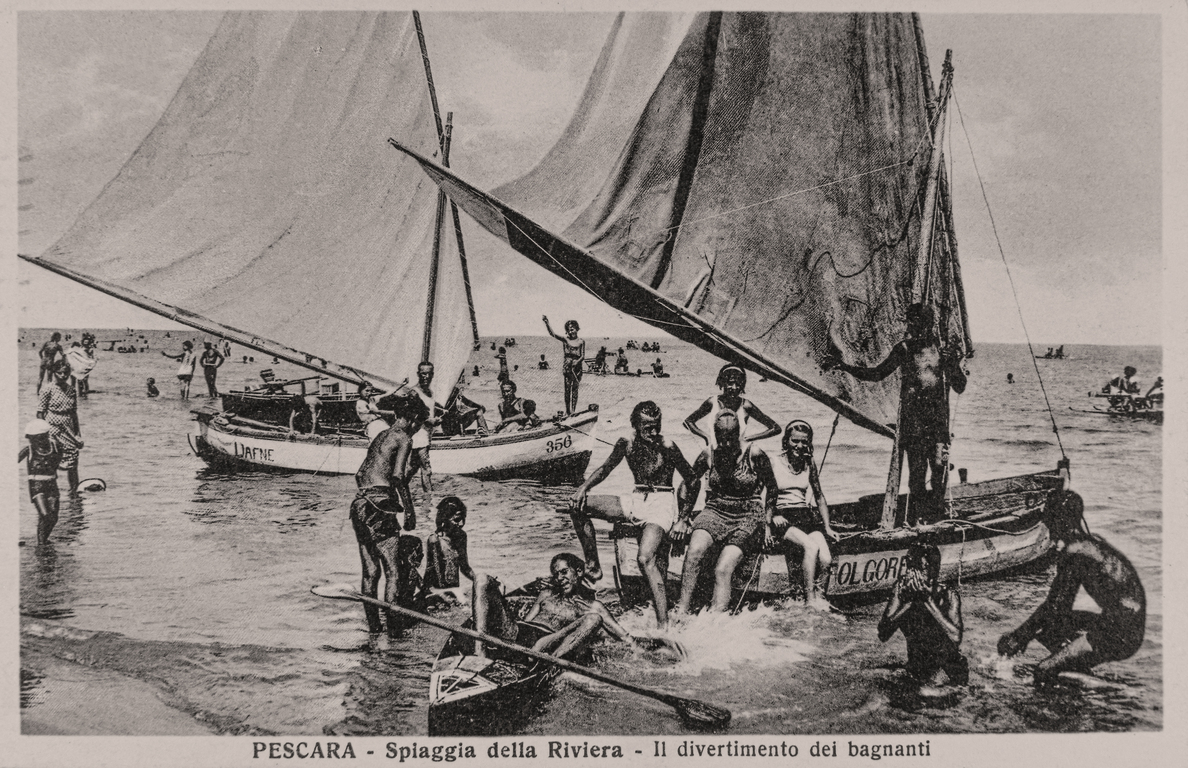

The diffidence with which coastal dwellers were viewed by other social classes did not prevent them from establishing close economic relations with the surrounding area. So when rail connections brought growing numbers of the new middle classes to the coast – first because seaside holidays and heliotherapy to fight the spread of tuberculosis and rickets became popular, then because industry and trade traffic intensified – in the closing decades of the nineteenth century, it was precisely the growing demand for fish that increased the number of boats and residents in fishing villages.

and the chance to sell these products quickly even at long distances thanks to the railway, supported the growth of new fishing villages, thanks also to the arrival of new fishing families from various Marche towns.The choice of the location and the settlement criterion of the new seaside villages was not dictated by urban planning models but followed the spontaneity of a profession disconnected from the territory, in direct contact with the sea, on the beach and on the docks where people lived and worked mainly outdoors, covering previously empty areas.

The inauguration of the Adriatic railway in 1863 and the subsequent trans-Apennine connection with Sulmona in 1873, and finally with Rome in 1888, brought a substantial influx of inhabitants from the Abruzzo hinterland to the coast, attracted by the dual prospect of retail trading and the new seaside resort business. The migratory movement also involved the same hill towns overlooking the coast – Castellamare Adriatico, Giulianova, Silvi, Francavilla, Ortona, and Vasto – where new towns developed close to the beaches, in shopping areas around rail stations and residential neighbourhoods overlooking the sea. The high demand for fish to be consumed by rich holidaymakers during the busy summer season,

The fishing family dwellings at the time of the paranza trawl boats were very humble, often just one room or if there were two, the family was considered wealthy. The door opened straight into the kitchen, where there was a hearth for heating and for cooking food. Behind this a second area, sometimes merely curtained off, was the bedroom and was also where children were born. In a corner of this there were holes in the floor connected to cesspools where excrement fell, or it might be collected in clay chamber-pots with two handles and a lid. Dim lighting came from by kerosene or oil lamps. The furniture consisted of a table, a wardrobe and a linen chest. The poor shacks leaned against each other and were made from the natural materials found in the area,

initially stones set one on top of the other, bound by a mixture of sand and lime, often gathered around small courtyards where domestic work was carried out and where there might be a well for drawing water. At the beginning of the 1900s, an improved version developed, made of brick, as well as houses for the boat owners, which consisted of a ground floor used as a cellar or storage room and a first floor, accessed by an indoor staircase or by an external ramp if they overlooked the courtyards. The new seaside villages generally did not have rooms intended for specific trade or craft business unless they were bakeries and wine cellars, popular in the afternoon when the weather was bad and it was impossible to go out to sea, or during festivities.

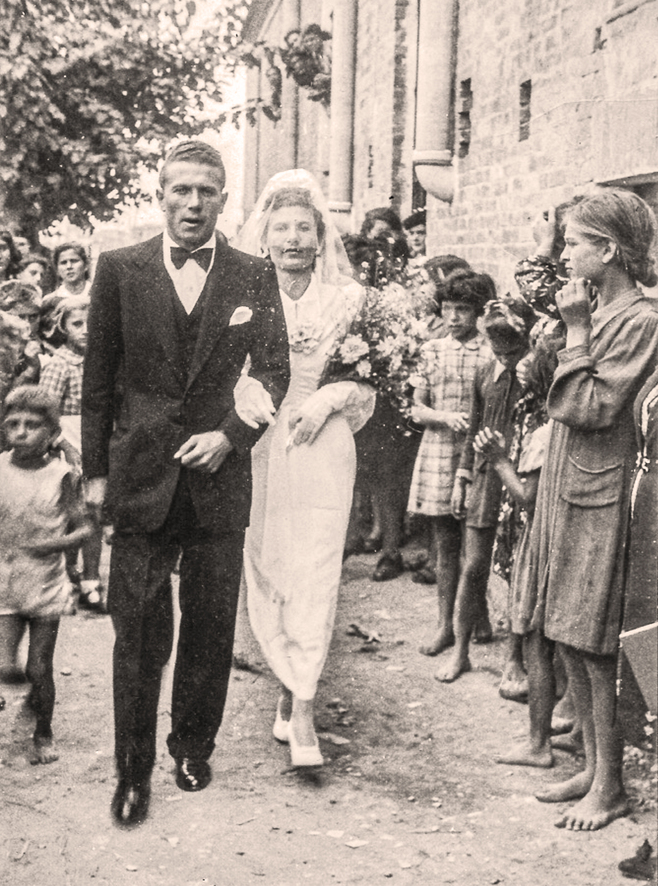

The next day, the bride’s trousseau, including the dresser and kitchen units, was loaded onto a cart decorated with ribbons and kerchiefs, and transported to the future marital home. The dowry was accepted by “his” mother and first-degree aunts but the bride did not accompany the cart. Saturday afternoon was dedicated to the “gifting” ceremony when the bride and groom, in their respective homes, welcomed wedding guests. A table of biscuits, sugared almonds and homemade liqueurs was set in a room where a lace ribbon was attached on one wall for hanging the cash given to the bride and groom, everyone knew the amount given by each guest; other gifts were arranged with greeting cards on another table. At 9am on Sunday morning, the actual wedding ceremony began at the bride’s home, when the dressmaker brough a white gown, dressing the bride with the help of her assistants. The carriages arrived at about 11am. The best vehicle was for the bride, with her father or brother; the second best was for the families of the two betrothed, and in the last, the groom sat with his mother or with an aunt and uncle. The bridegroom entered the church first, on his mother’s arm, and waited for his future wife in front of the altar. The bride’s mother did not attend the ceremony because she was busy preparing the wedding breakfast at home with the women neighbours.

At the end of the ceremony, the couple took their seats in the first carriage and were followed by the others. On the way from the church to the bride’s house, where lunch was served, the occupants of the carriages threw handfuls of sugared almonds to the acquaintances they met. The two newly weds were greeted by their respective mothers, who embraced and kissed the bride, while a shower of sugared almonds and flowers poured over the happy girl.

(text provided by the multisite port museum – FLAG Costa di Pescara)

In these villages, marriage was almost always between the offspring of fishing families. These were small communities where everyone knew everyone else because their occupation conditioned their habits and underpinned their pace of life. The couples developed in adolescence, exchanging their first interested but silent glances for fear of being discovered; For a long while only their eyes could express their attraction and just before leaving for military service, the young man would finally ask his future fiancée for a chat, and she would agreed to the chat, arriving at the date with a friend. The youngsters then confided their “secret” to their mothers, who almost always gave their consent because the families knew each other. From that day on, the girl was required to respect her future mother-in-law, whom she already called “mam”, and she was allowed to visit her in-laws at home when her fiancé was away. His mother would then go to her future daughter-in-law’s house to set a date for the official betrothal, which took place during the young man’s first leave. Only after the ceremony was the fiancé allowed to enter his betrothed’s house and extreme courtesy and respect were expected of him! The wedding date was set when the young man completed his military service and had managed to save enough money to buy a bedroom suite. The “nuptials” were celebrated on a Sunday and most fishing boats stayed on dry land because almost all the sailors took part. On the Thursday before the wedding, the bride’s trousseau was inventoried in her home, with the groom’s mother looking on, then bridal goods went on display. The bride-to-be welcomed her friends and the older village women with a small glass of homemade liqueur and a few sugared almonds.

Immediately afterwards, the copious banquet began with thirty courses, all meat: fish was never consumed. After lunch, the dancing began. You could see tipsy “buddies“ in their Sunday best – worn only two or three times a year – as they asked for a dance with the bride. The feast lasted many hours and it was not until about midnight that the bride and groom were taken to their new home. But it still was not time for them to alone because the groom’s friends would then turn up under the windows to serenade them. The groom had to get up, welcome them into the kitchen and offer them liqueurs, wine, biscuits. The joy of being “alone at last” came sunrise!

Indeed, the induction into the seafaring life took place very early, around the age of eight: a son followed in his father’s footsteps, embarking as a murè, a deck boy for a skipper. A stoical way of life based on being trained to shoulder hard work and be competitive, because they had to make the parone – the skipper – notice them so they might be given some of the catch that he distributed to the fishermen as he pleased. Rivalry within the category proved to be a qualifying element for exercising the profession and became a fount of identity and pride, sometimes beyond purely monetary motives. Then again, fishing is a form of natural predation that intrinsically generates antagonism with other competitors, not only outside the group but also within it, to establish hierarchies. Nonetheless, competition is equally and deeply transformed into complicity and solidarity in case of danger to the individual or social group of a origin.

D’Annunzio, in his Primo Vere, wrote that “The sea is... the Homeland of the free” and it was precisely the spirit of independence – which could not be classified into employer or employee classes – often rendered fishermen hostile to any form of grouping, whether legal, administrative or trade union.

The dominant intermarriage system intensified both the cultural and physical isolation of these communities. Indeed, the development of fishing villages, driven by the growing coastal population and increased demand for fresh fish, resisted all the forms of integration that had been stimulated by evolving customs in the early 1900s with the expansion of seaside settlements. Fishing here can be considered a family and social tradition that went beyond the connotations of economic activities, engaging the entire community because of the unique pace of life, cadenced by the timetable of departures and returns, so different to urban agendas. The clusters of shacks set in small courtyards remained silent during the day because menfolk went to fish at sea from an early age, and the shores and docks came alive at sunset when the boats unloaded their catch. Not only did work on the seas offer a way to survive but it also represented an identifying and conscious dimension of status, flaunted proudly and with passion.

Until after the Second World War, fishing communities continued to express a very closed attitude towards the outside world, aware that their model of economic and social structure was different to the surrounding environment. In the meantime the latter changing and taking on urban connotations. On the other hand, the nineteenth-twentieth century public administrations, with their distinctly bourgeois management, showed little interest for a long time in wanting to penetrate these groups and involve them in the urban development that was characterizing seaside towns. Even today, in collective imagination, “fishing folk” are considered with some concern and superiority by urban dwellers, perhaps preserving the memory of a time gone by.

The perceived foreignness of maritime culture has not even aroused the interest and attention of scholars and educated classes for safeguarding and preserving the last material and spiritual traces. Unlike what happened for crop and livestock farmers, perhaps closer to the bourgeois concept of land and territory, in the past it was not possible to go beyond the romantic vision of coloured sails and seascapes illustrated by painters and described by poets; Later, since seafaring people could not be considered a subordinate social class engaged in the fight for recognition of worker rights in the industrial and farmer proletariat, even Gramscian historical perspective – prevalent in demo-anthropological studies – cast doubt on the existence of a defined maritime culture. The interpretative embarrassment, perhaps more so than the small number of fishermen, in addition to the rapid deterioration of the group’s material culture, probably explains the few museums dedicated to traditional seafaring and the scarcity of artifacts preserved today, despite the fact that Italy is surrounded by sea.

Knowing how to predict the weather reliably meant not only ensuring fishing in the best conditions, but often also the safety of the fishermen. The Apennine massif was observed daily and offered fundamental clues, combined with assessment of the night breezes. In summer, when large white clouds formed high above the peak, it was a sign that the day would be fine and in the evening the breezes would follow the sun. On the other hand, when the clouds skimmed the peak and were darker in colour, a change in weather was to be expected within two days. Clouds the same colour as the mountain, clutching at the outline of the peaks, without detaching themselves from them, was an unmistakable sign of imminent bad weather.

The most feared wind was the southwester – known as the garbino in Abruzzo – because it made life difficult for the paranza trawl boat, having to face gusts that blew very violently from inland and making return to shore beach very tricky.

(a loose interpretation of Francesco Feola’s Paranze)

The precarious seafaring conditions, connected to the unpredictability of water and wind conditions, meant observation of nature was crucial as was the experience of older sailors who knew how to interpret what they saw. The looming presence of the high Apennine peaks connected to the coast by perpendicular valleys, which plunge into the sea just a short distance from the mountain foothills, are a feature of the Abruzzo landscape, constantly traversed by land and sea breezes. These outright channels of air continuously influence the direction of the waves and the conditions at sea by the coast, also because the waters are shallow and the change in weather and sea conditions is quite sudden.

When the southwester suddenly dropped, as quickly as it came, it left the boats at the mercy of the long waves that put a strain on hull resistance. Another situation that was troublesome was called the rivaddure, namely the rapid transition from the southwester to the tramontana or north wind. Extreme was necessary because the violent gust of wind could hit the masts while the boats were held back at sea by the heavy trawl nets.

The elders passed on their experience orally, quoting many proverbs, derived from observations made over the centuries, defined with a few rhyming words to make them easier to remember. Of course, these proverbs varied from area to area, depending on the form of the mountains and the names given to the district.

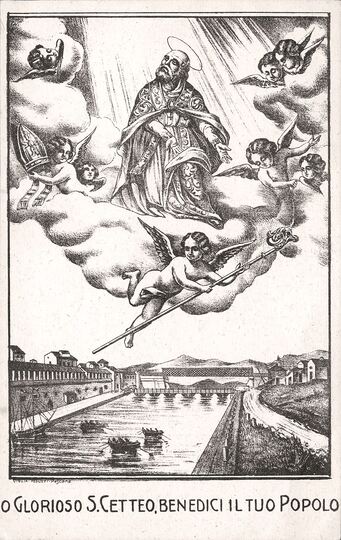

While the knife slowly mapped out the mark, proceeding counterclockwise and without interruption, the sailor in charge of the ritual had to recite a exorcising formula that could only be handed down by elders on Christmas Night. In Pescara, the wording was: “In the name of St Ceteo/and the Virgin Mary/say three high masses/so that you melt away/ like salt in food!” Then the person in charge dropped his trousers towards the twister, shouting: “arse to wind, let’s make flying babies!”. Only the firstborn son could share the divinatory skills for connecting with spirits, because their parents had been virgins until their marriage (a sign of purity that allowed them to come into contact with the other world, like vestal virgins).

According to the symbolic outline that made the hull an animated subject, the launch of the boat also had to ensure it entered the sea by the stern, allowing the paranza to “see” and remember the beach from which it had departed and to return there. Naturally the baptism of the boat was a ceremony that included religious rites, such as the blessing of the hull to protect from the dangers of the sea, together with more archaic elements aimed at invoking earthly protection by a figure chosen to be the compare – the “godfather” of the paranza, who was then replaced by the figure of the “godmother” during the launching rite.

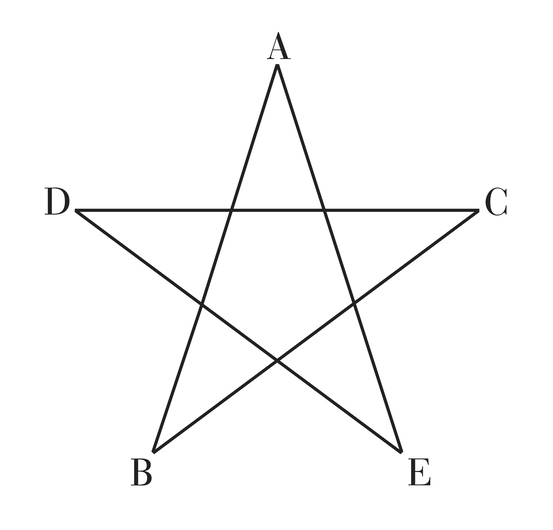

When unforeseen difficulties could not be remedied by drawing on the wealth of true experience, recourse was made to the symbolic survival practices typical of folk culture: rituals exorcised the event were put in place. An example of this tradition are the formulas adopted to “cut” lu scijone, a waterspout (twister) that was believed to be generated by evil spirits, demons in the form of men or women born on Christmas Eve. The male scijone was tall and slender; the females, who was more dangerous, were recognizable by their broad “hips”. To avert the danger, a sailor, the eldest son on board, had to face the twister and trace on the hull (or only symbolically in the air) the “sign of Solomon”, namely the five-pointed star (symbolic representation of a human body) by sticking a magic, black switchblade knife – “the knife of St Liborius” – in the centre.

This ceremony took place in similar forms all along the mid-Adriatic coast. In the symbolic transposition, to which the practices of magical protection resorted, the boat could take on the appearance of an anthropomorphic subject on which to affix or paint large red (against envy) eyes in the shape of an inverted comma, whose pupils were the two holes for the bow anchors (occhi di cubìa). An ancient tradition, widespread throughout the Mediterranean, tells that these eyes were to “scrutinize” the route to avoid obstacles at sea.

In the context of symbolic rites, propitiatory intentions are sometimes mixed – such as those tiny scapulars containing different substances and amulets like seahorses – with more distinctly defensive purposes, where the sign of the cross, the blessing, and the saints are a syncretic invocation to protect against danger and to tame the sea, an alien dimension with respect to the land. There are similar rites when rescued sailors who escaped death would commission local painters and artisans to paint votive offerings for grace received, usually showing the name of the fisherman, date of the event, the depiction of the dramatic event with the stormy sea and of the saint or Our Lady who saved them.

Faith in God and in the patron saint were often the fruit of a combined religions, a tightrope of sacred and magic, superstition and faith, within which there was room for Christ and for the magus, for the blessed palms placed at Easter on the masts of the boats and for the amulets to be worn or carried on board to ward off the evil eye. Here good luck charms came from the sea and the seahorses took the place of the red peppers the peasant communities. Above all, destiny loomed, an oblivious manager of human events from which no one can escape and accepted with fatalistic resignation by those whose lives were constantly at the mercy of danger and uncontrollable weather conditions.

Even the traditional fried fish offered as street food on such occasions has lost the sense of the community sharing the catch and become a kind of welcome to the tourist who drives these foodie festivals. Yet, in the colourful, noisy funfairs that characterize the most external side of the festivals, we can still see the sense of defiance of danger and fear, a display of strength and vitality typical of the young people who flock to them in the evening, almost wanting to remind us that the most ancestral mechanisms that underlie our behaviour and forms of expression survive even in a culturally globalized society. The rediscovery of our identity roots, popular in recent times as a reaction to standardization, must not only be an opportunity for collective memory but must serve to rebuild the connective tissue of communities and social life in new forms.

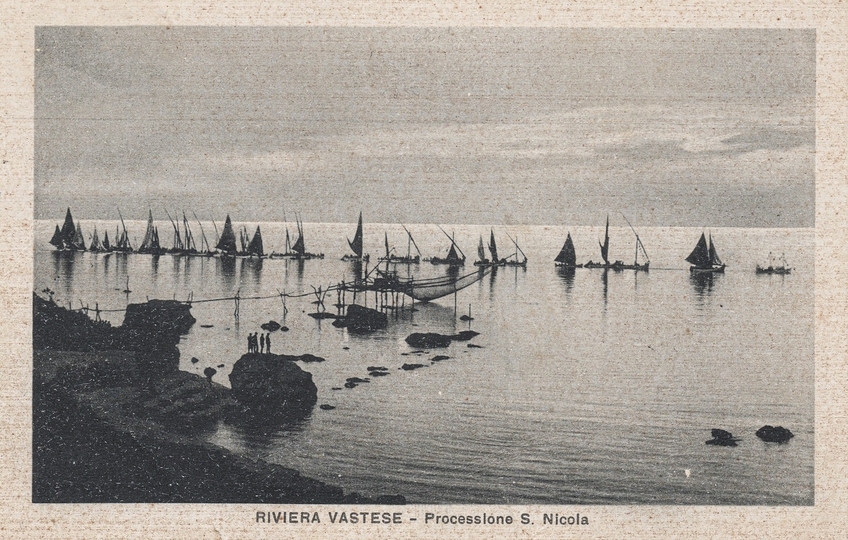

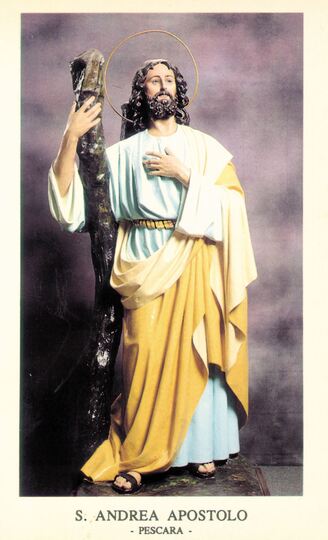

The fishermen only really had days of rest on the feasts for local patron saints and the “circle of hell days”, which coincided with the main religious holidays. November 2 was especially respected because it was believed that the bones of the dead would be fished. The dates of “circle of hell days” traditionally thought to be disastrous (the word etymologically connected to dis-aster), namely when unfavourable alignments of celestial bodies were a bad omen. These dates were usually the delicate moments of transition from one solar phase/season to another, or when some tragic event was recalled, like the historic tsunami that occurred on the Abruzzo coasts at the end of July 1627. In Pescara no one went to sea at Christmas and Easter, on the anniversary of the patron saints Ceteo and Andrew, and above all on the nights of All Saints and All Souls. On those days superstition required to do or not to do something that would ingratiate the person with the Divinity, where not going to work also became the occasion for ritual ceremonies repeated year after year.

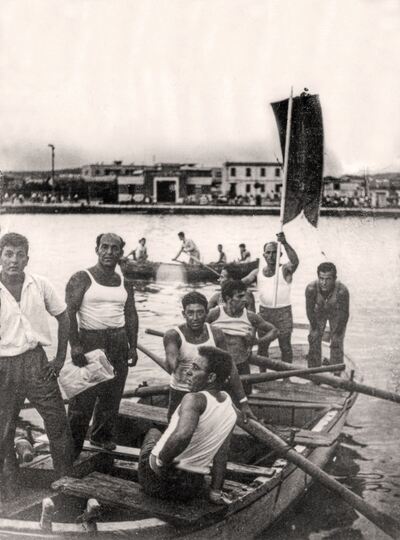

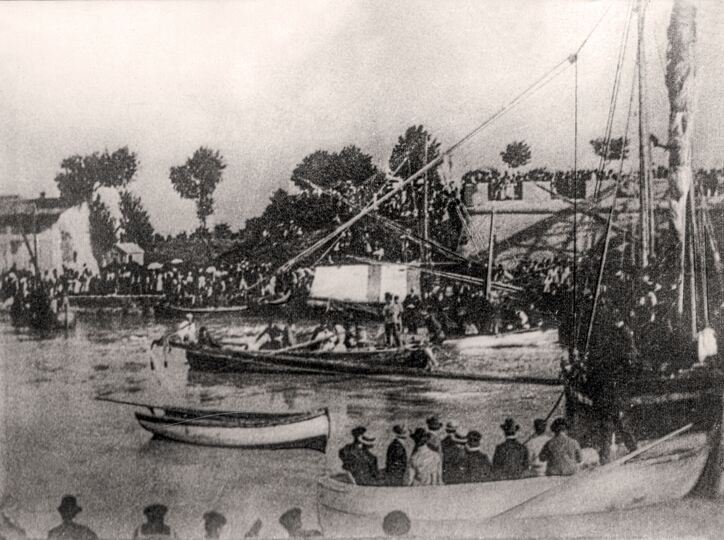

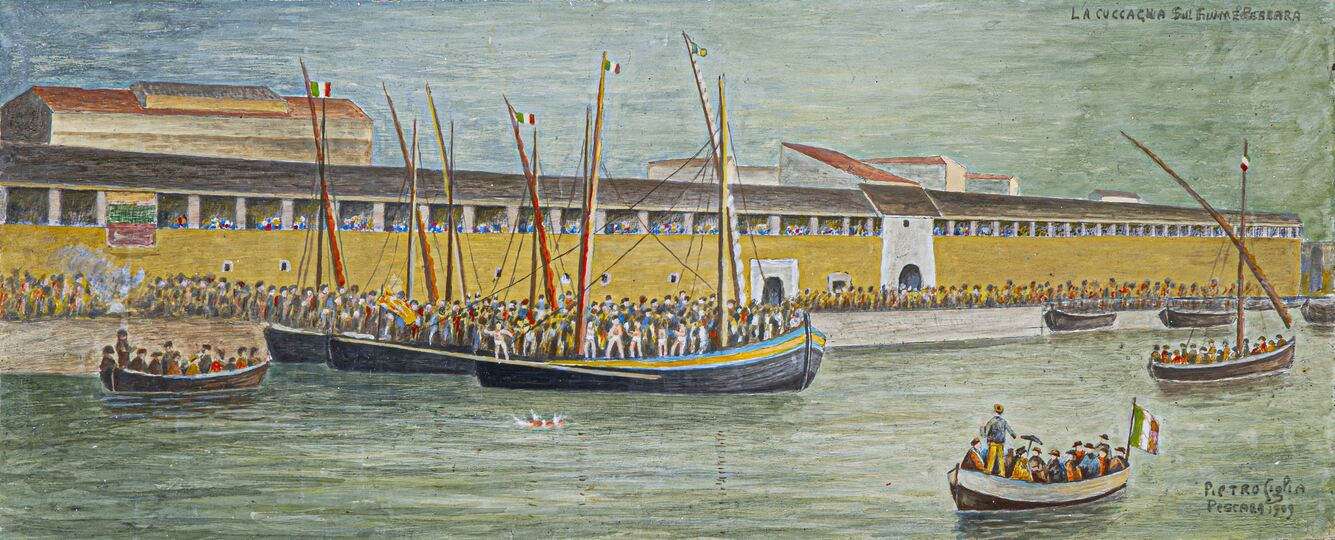

The festivities had not only a religious significance but were also a form of aggregation identifying the village community, an opportunity to parade attention-seeking both by individuals or groups to which they belonged, and to exhibit strength and vitality. The spirit of competition connected to being a fisherman strengthened the customary tests of virility and resistance that young men had to demonstrate on such occasions. Rowing competitions between rival boat crews, maypole challenges, or even just who could the most red-hot spaghetti were not just a chance to have some fun but clear signs of the deeper social motivations that such events had for the fishing villages and beyond. Nowadays the festivities have progressively lost their ancient symbolic meaning and are no longer occasions for sharing emotions and celebrating local identity, the collective consciousness of being part of a sacred history. The façade of the feast day is now mainly for an audience of tourists.

Map of maritime festivals

Discover them by clicking on the highlighted locations

In winter the use of dried fish was quite frequent, rehydrated in water and cooked in various ways. As in all working class homes of the time, there was no shortage of salt cod and stockfish but local species such as dogfish and fragaglia (small mixed fish), octopus and cuttlefish were also suitable for drying.

There was rarely a cooked meal at midday: the children were given a large slice of bread and olive oil with some fruit because the main meal was eaten in the evening, when the men returned from fishing. During the summer, when the fishing boats stayed at sea for several days, the women waited for the boatman who brought the catch to shore for auction to return. They were given a basket of there share of the catch and went home to cook the fish without tomato sauce, with a little rice or cooked over embers to save oil. The brodetto or fish broth was only cooked when the men came home and this was the only time wine was bought. The preparation of this typical dish at home was different from the way it was cooked on board (see the Pescara boat brodetto in the multimedia dedicated to fishing boats and life on board) and the recipe varied from one area to another.

The consumption of pulses with fresh homemade pasta was frequent on fisher family tables and there was always fruit. One of the most interesting recipes, an example of the ancient culture of food preservation, was based on marinating fish – calpisèlle. Now no longer made and replaced by the more common scapèce, this was a vinegar sauce used to facilitate preservation after frying fish to destroy bacteria load and block the proliferation of fungal spores. Drying and marinating were the two main methods of preserving fish, caught in abundance in the summer months and consumed in winter when quarry and trips out to sea became rarer, so popular custom required preservation of food supplies and nothing was wasted in the perennial struggle for survival.

Below is the typical recipe for brodetto fish broth as it was cooked in Vasto homes, shared by Francesco Feola in his book Paranze:

“Begin by pouring a good amount of extra virgin olive oil into a large enamelled clay pan, stirring in a measure of finely chopped garlic, parsley, basil, and green chillies, then fresh tomatoes were added or tomato preserve in winter. When everything was almost cooked and the liquid came to boil, the fish was added, starting with the toughest types, medium-sized and as much assortment as possible to guarantee a variety of flavours – red mullet and cod, sole and megrim, large and small squid, the tenderest of cuttlefish, bandfish, and some mantis shrimp for extra taste. The addition clams and mussels in in Vastese brodetto is quite recent.”

Another recipe from Francesco Feola’s book Le Paranze, for the preparation of Vasto’s traditional calpisèlle:

“Calpisèlle was traditionally made at Christmas and the best fish was chosen: cod, cuttlefish, squid, piper gurnard, and mullet, all quite large in size. Once the fish was fried, it was layered in a tureen or in a special barrel, the cognotto, and boiled almonds, pomegranate, pine nuts, cherries, peppers, capers, rock herbs, green beans and pickled vegetables were placed between the layers. Apart, vinegar and with boiled must were cooked with aromatic herbs (rosemary, sage, bay leaves) and the mixture poured into the tureen or barrel, making sure that the liquid was boiling hot and that it penetrated to the bottom of the container so that all the fish was saturated.”

Sviluppato da Microware s.r.l.

www.microwareitalia.com