The Paranza

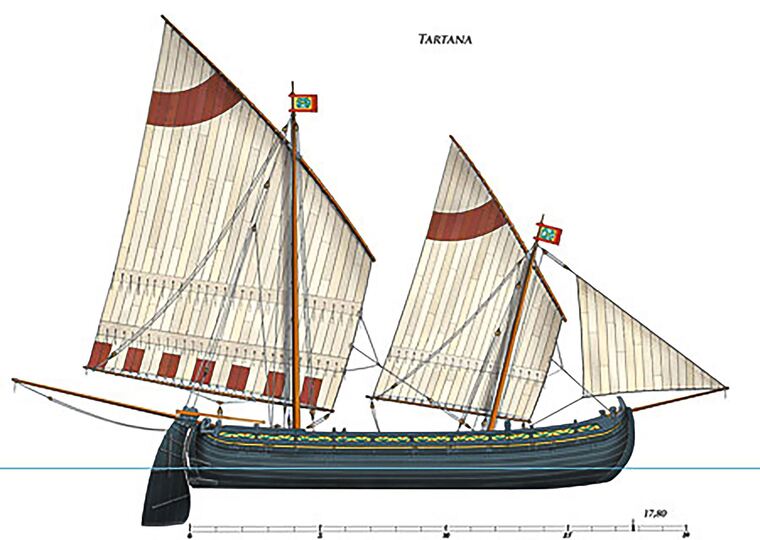

Fishing in pairs made it possible to catch much more fish because the mouth of the net opened wider and the driving force of the two boats, powered by sufficient wind at any pace, enabled them to cover longer distances in less time. Conversely, the old tartana technique, using the large trawl net stretched between the bow and the stern, had to be towed only in crosswise progress to catch sufficient wind thrust on the sail, so expeditions were only during spring and summer, when winds and waves made it less complex to steer equipment.

Indeed, with the progress of medical sciences in the Age of Enlightenment, seafood – previously considered a “poor man’s food” for the popular diet and eaten on days of “penance” or maigre days – was re-evaluated for its nutritional qualities and consumption rose, especially among the bourgeoisie.

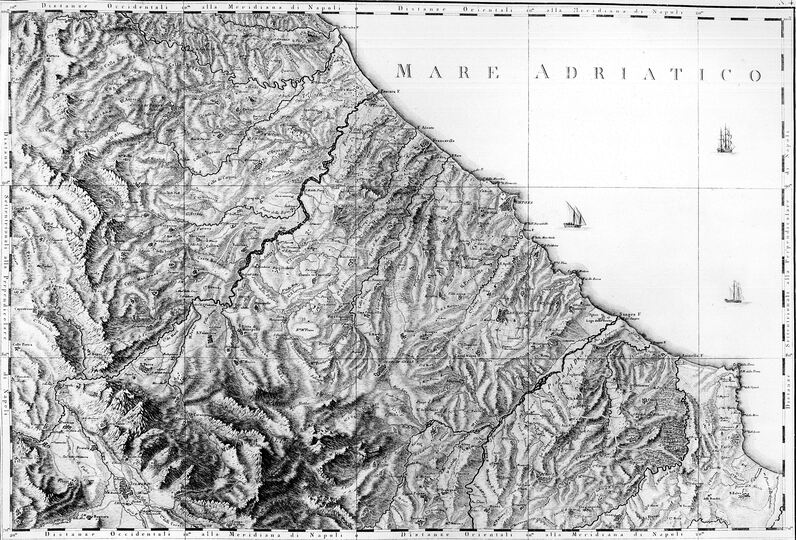

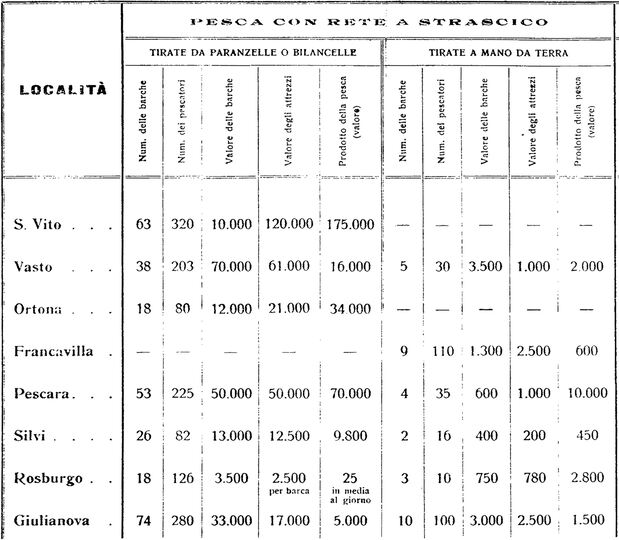

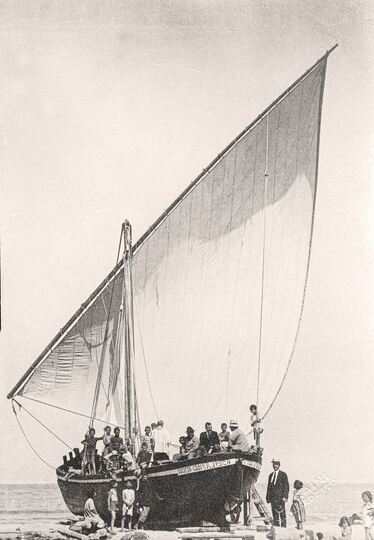

The Paranza was the typical fishing boat widespread along the mid-Adriatic from the mid-eighteenth century, heralding a true revolution in fishing techniques because the introduction of trawling practiced in pairs by smaller boats, with lower costs and more manoeuvrable in than the forerunner tartana, favoured the development of a new navigation system that made it possible to face open seas in every season. This made strides in yield compared to traditional fishing systems based on a single vessel.

The paranza and the barchitto, typical of the Abruzzo and Marche coasts, and the bragozzo widespread in the upper Adriatic, became the new boats, costing less and increasing catch, leading to the numerical growth and territorial expansion of the flotillas to respond to demographic growth and changed eating habits among the population.

Added to this was the development of a new system for preserving fresh fish, with the use of ice and snow which allowed the distribution of the perishable product to inland markets, even in summer.

In 1797, with the end of the Republic of Venice, the merchant navy in the Adriatic declined and this new type of boat, with the related fishing techniques made it possible to develop the fishing activities carried out by private individuals and small owners, leading to specialization of the trade and contributing to the subsequent migration of many fishing families from the historic navies of Chioggia and Caorle towards other Adriatic ports, where they found new areas in which to settle.

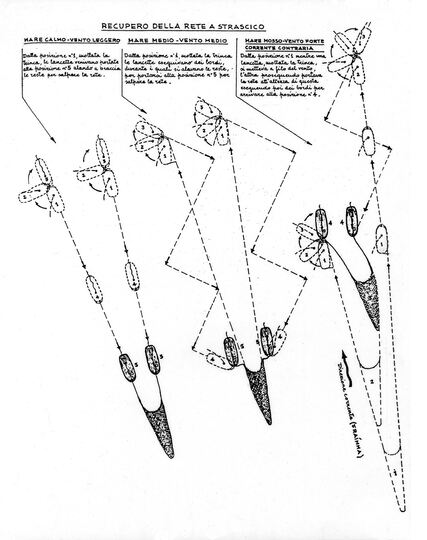

The windward paranza was commanded by the parone the skipper who guided all manoeuvres, even on the leeward boat with simple gestures whose meaning was handed down by custom. During fishing, the distance between the two hulls was about 40 metres so that orders could be clearly observed or heard and put in place in unison. The paranza moved away from the shore for no further than 10–15 sea miles (about 20km). Once in the fishing area, after tying the sail, the other boat was called to place itself at a close distance and the libbano – the large rope that dragged the net sack – was exchanged by launching a small decoy line (called a ciucciarello).

When the time came to cast the net, the skipper called out to the twin boat and ordered it to get ready. The sails were hauled in to slow down the pace and make it easier to recover the reste, carried from the stern to the bow where the giovane – the youngest fisherman – would wind them around a mancolo, a sort of knob-shaped bollard. Upon arrival at the libbano, the large rope that preceded the net, the fisherman whose job it was to recover the sack waited for the two boats to come together, then manually collected the bundled-up net, coupled with the other, hoisting it until the full sack was loaded on board using the trysail tackle. Then the fish was sorted:

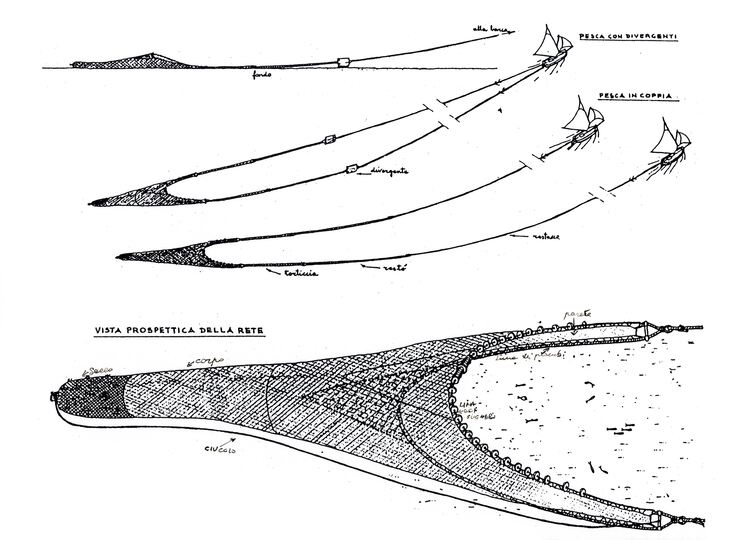

The Paranza – trawl boat – derives its name from the fishing method, which was practiced in pairs with two boats (“al paro”) towing a trawl net (called a tartana) on sandy, shallow seabeds. This technique forced the crews to steer the fishing boats in complex sailing manoeuvres that had to take place in perfect synchrony, to keep the hulls always at the same distance, with the long cable that joined them passing through the net and which had to be taut and open and all times.

After having connected the paranze and lowered the sack (lu cucuolle) the parone decided the number of reste to be spun into the sea. The reste were smaller ropes, a little over 100 metres long, and the number used depended on the fishing depth: at about 10 metres deep, for example, 4–5 strings were connected. The presence of possible obstacles and the need to defend themselves from dolphins suggested the use of protective nets with large, tarred mesh mounted to protect the terminal sack – there was lu tramione or ‘ndramicchie da talifaini against the voracious attacks of these detested mammals. Only a single cast of the trawl net lasting six or seven hours or one of four hours followed by another of two were possible.

the better quality was piled up on the bow to be sent for sale while the lesser quality was used to prepare the scafetta, the payment in kind for each fisherman. The time of return from fishing varied with the changing wind and seasons but for normal daily trips the boats returned in the afternoon, while in periods of intensive fishing, in spring and summer, they stayed offshore for weeks at a time.

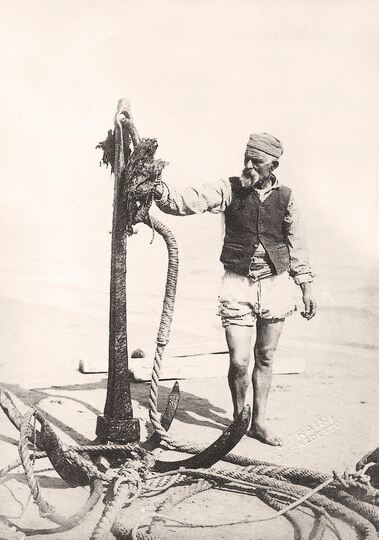

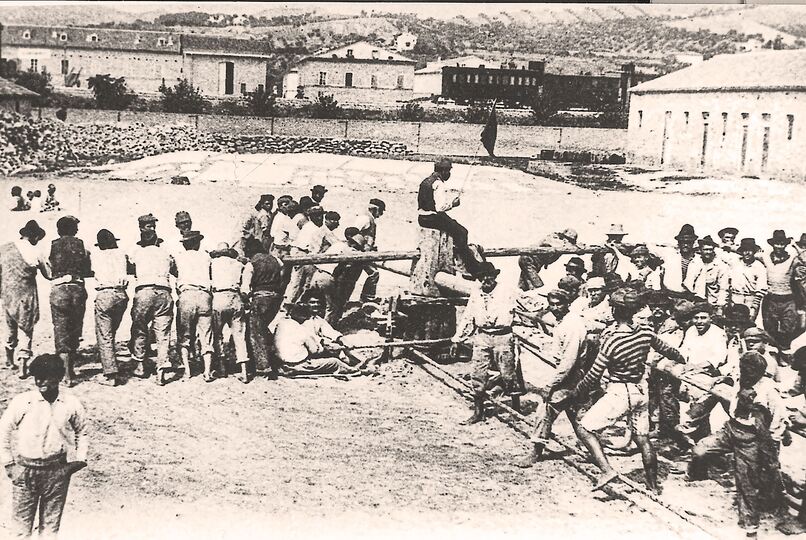

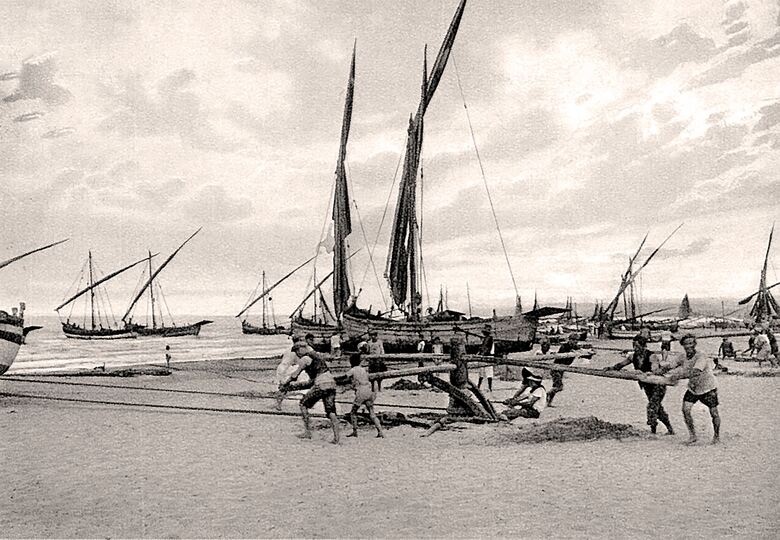

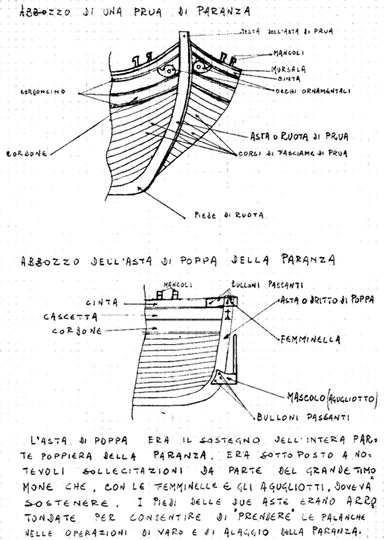

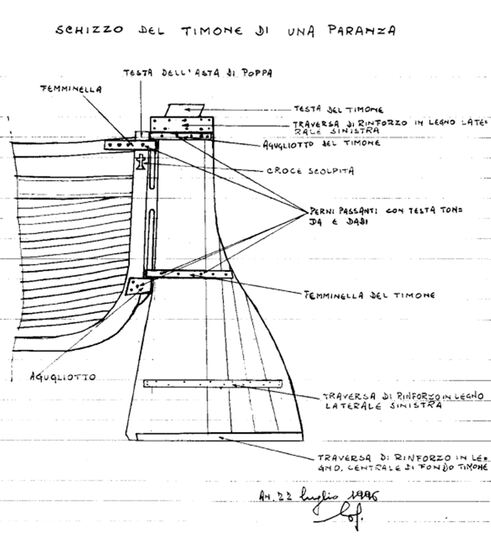

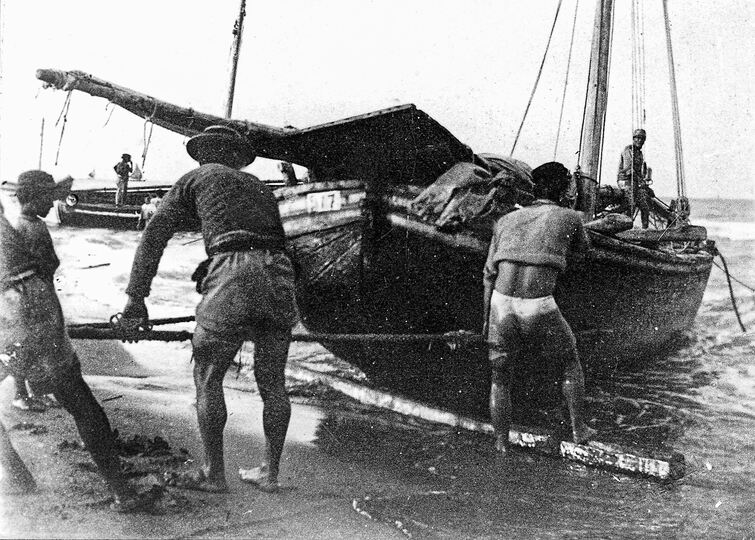

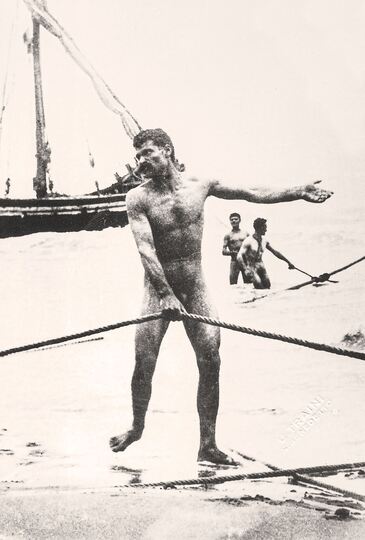

The boats were anchored at sea in the vovara – a dip in the sand between the scagno – sand bar – and the shore, lowering an anchor to the fore and bringing the other two heavy stern irons ashore to be buried under the sand. In case of bad weather it was crucial that the boats could be dragged ashore using the regagna, a large wooden winch fixed to the shoreline, sliding them on palancole, planks greased with sheep fat. This was why it was impossible to mount a fixed keel that would avoid driftage so this function was entrusted to the rudder which was thus of a considerable size but could be raised and lowered without leaving its housing.

One of the most evident features of this type of vessel was the massive “duck breast” bow, higher than the bulwark line to protect from the waves when sailing but flattened with a large end tuppo or knob, which combined with the two hungered relief“ eyes” almost to depict a humanized face that saw the dangers and obstacles of the sea.

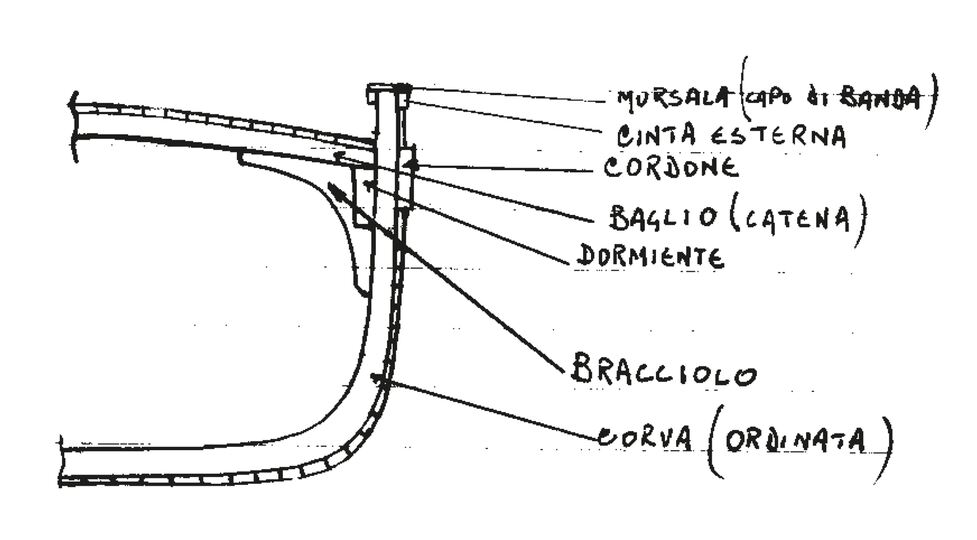

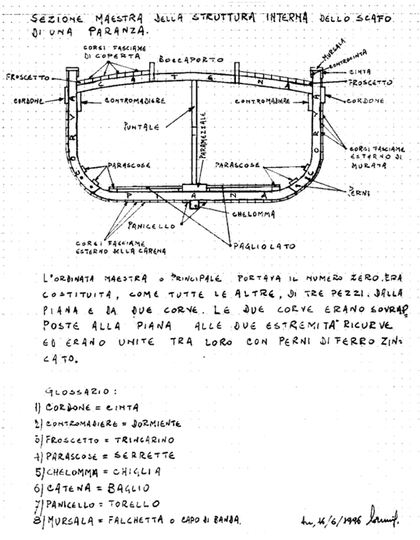

Handcrafted from oak by local shipwrights, with techniques handed down from father to son by word of mouth, paranze and similar local boats like the two-masted versions called barchitti and the smaller lancette, were characterized by a slightly bulging keel always flanked by two parallel support bases. The almost flat bottom, in fact, was perfectly suited to the shallow, dangerous seabed of this stretch of the Adriatic, with few safe landing places in the event of cross winds.

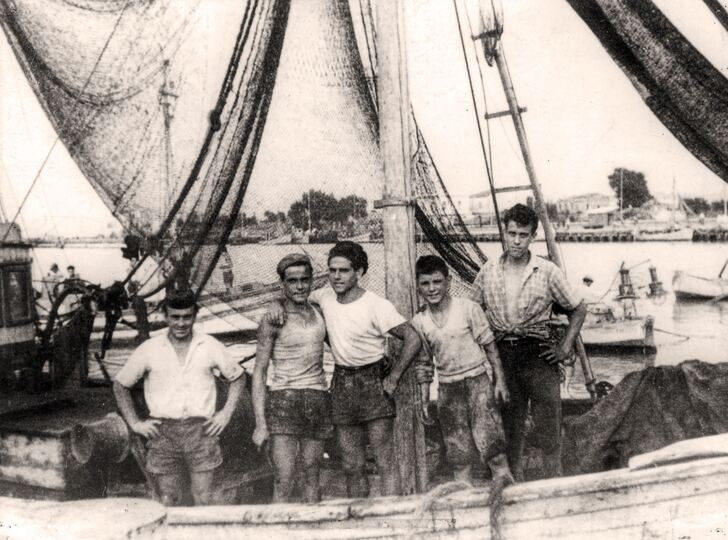

There are also adaptations in boat size for each type, which could vary according to the different needs of the purchaser, who might be a shipowner or small owner/skipper, which came about especially after the First World War, when the great crisis caused by the prolonged stoppage of fishing in the Adriatic and the decrease in the number of fishermen, reduced the length of a paranza from the 15–20 metres that they could reach to around 10 metres, with crews that dropped from over 10 to 6 men, which meant more private and family-oriented management.

The hulls were regularly brought ashore for caulking, a waterproofing treatment entrusted to expert artisans who used a pegola or pitch made from refined pine resin that served as bond and sealant.

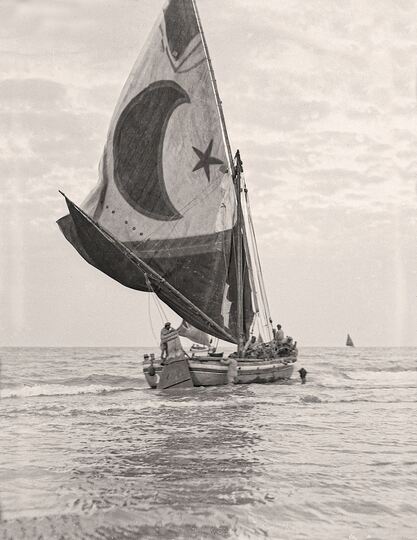

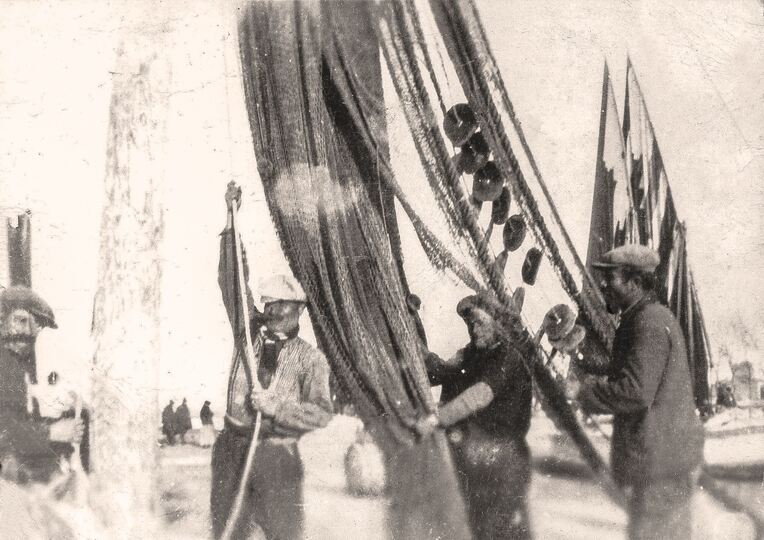

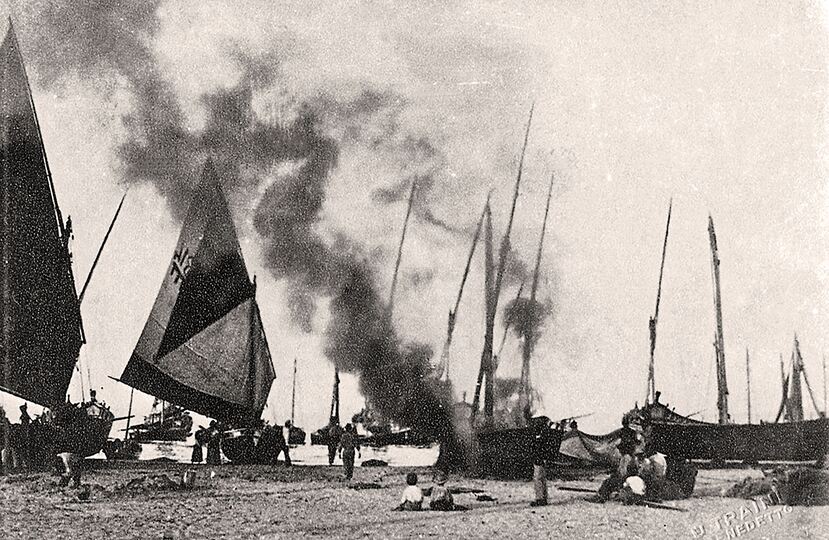

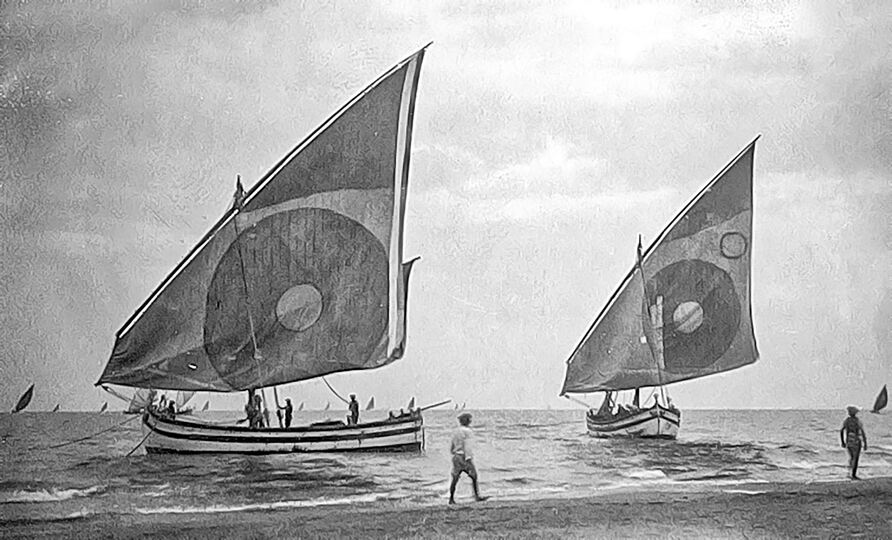

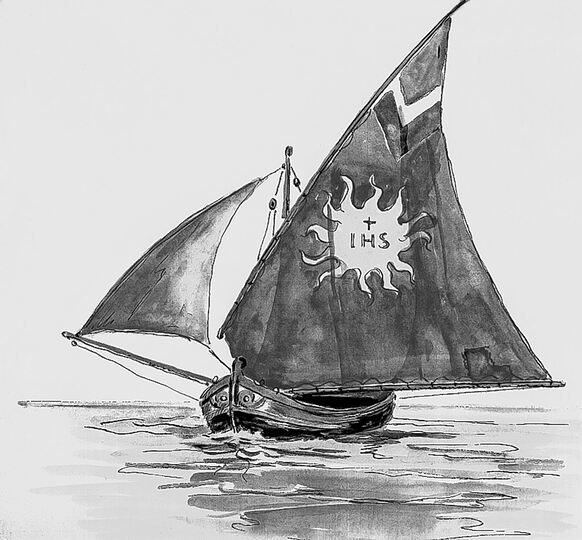

Once assembled, the sails were painted with yellow ochre or reddish natural earths and decorated with symbols in the centre so they could be recognized from afar when they were returning to shore with the catch to be unloaded. The sails lasted three–four years then had to be replaced.

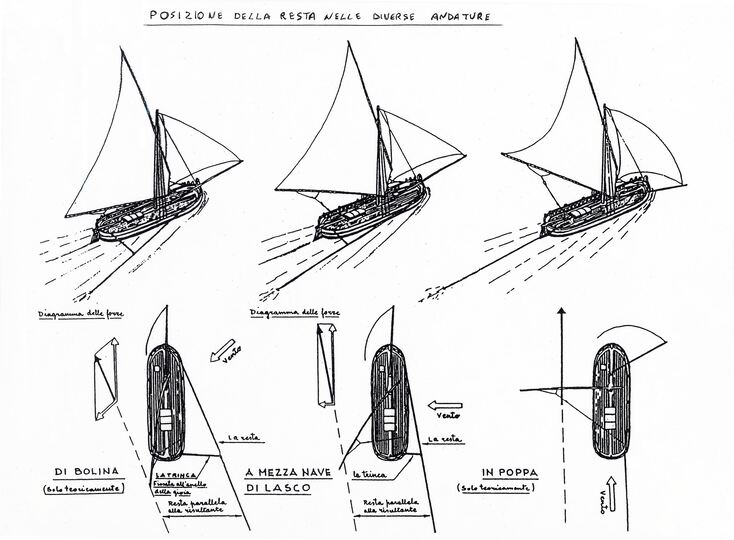

The lugsail is one of the so-called fore-and-aft sails that make it possible to sail close to the wind and therefore tack along the diagonal and sail against the wind. The peculiarities of the types of sail have often been confused because the nomenclature adopted by fishermen called the lateen sail a lugsail and lugsail a lateen sail.

Another essential component that characterized the paranza were the large sails that could tow the heavy trawl nets. The most expert local fishermen stitched the sailcloth, ordering rolls of six-thread cotton twist canvas from Ancona and cutting strips of fabric of increasing length, placing them side by side and sewing them vertically along the selvage.

The paranza originally had a single mast with a lateen sail but gradually a third and more manoeuvrable sail also came into use on the Abruzzo coast, often in addition to a second smaller sail at the bow used for stern sailing (the palaccone kept out of the cacciafuori, forerunner of the modern riding boom). The Venetian-inspired lugsail had an irregular trapezoidal shape and was inserted between two spars, tied to the masthead at a third of the total length of the upper yard.

Inside the paranza we would have observed a barrel of drinking water tied to the side; canvas camp beds dangling below deck near the wooden crucifix and images of patron saints nailed to the base of the mast, an oil lamp hanging near the hatch and three or four sestole (or sessole) – large corner wooden scoops used by the murè, the cabin boys, to drain the water that built up in the bilge. In the bow there was the paioletto, a shelf above the bottom-boards that housed a berth above and wood and coal for cooking below, where it was sheltered. The fucone, a sort of quadrangular brazier, was inserted in a small hatch in the bow and covered with bricks, then filled with sand with a layer of ash on top. The stern paioletto was larger and the linguette, string and everything needed to repair nets and sails were kept under the berth. The hold of the paranza was a tidy area containing fishing nets, the bow sails, the panari and coffe (baskets for carrying fish), and the resta della speranza or spera – a long thick hemp rope used as a floating anchor to straighten the hull during the delicate manoeuvres when returning to shore in rough seas and to prevent the stern from being pushed sideways by the waves, endangering the boat.

La sciabica da paranza

Era la principale rete a strascico da fondo anticamente trainata da due paranze appaiate, composta da due bracci e da un sacco, collegata alle barche da una lunga serie di cime di diverso diametro. Il sacco veniva rivestito da uno struscio di rete più spessa per preservare il sacco da un consumo eccessivo.

Lu carpasfòje

Il carpasfoglie era una rete a strascico con la quale si prendevano le sogliole (le sfoje), i rombi, le passere e altri pesci bentonici che vivono nei fondali fangosi dell’Adriatico. Questa lunga rete a sacco veniva trainata sia dalle paranze che dalle lancette tipicamente durante la notte, navigando vicino alla costa e in parallelo alla stessa. L’imboccatura della rete era tenuta costantemente aperta da un palo di faggio di circa due metri mentre nella parte inferiore una lima di piombi laminati arava superficialmente i bassi fondali.

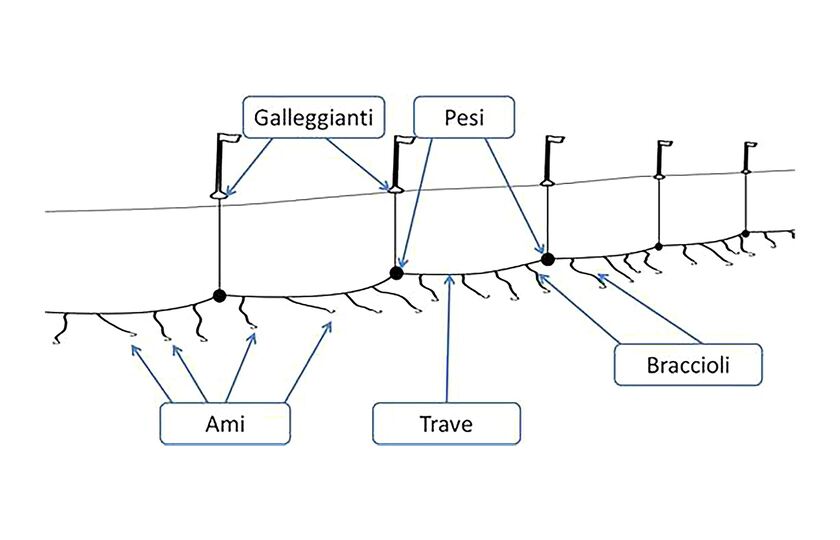

Lu palangare

Un altro attrezzo usato da alcuni equipaggi specializzati era il palancàro, formato da una lunga cima alla quale erano legati a distanza costante una serie di lenze sottili alla cui estremità erano fissati gli ami con le esche. I piombi e i sugheri erano posizionati in modo che lu palangàre rimanesse sul fondo, oppure a mezz’acqua o che galleggiasse, con la scelta di ami ed esche a seconda della specie bersaglio. Con il filo grosso di canapa si potevano catturare pesci di grandi dimensioni, fino a 100 chili, come il palombo, il gattuccio, razze, la vaccarella, la pastinaca, il dentice, il grongo e altri. Per questa pesca lu palangàre si lasciava in acqua tutta la notte.

they included the giovane, a younger man who was entrusted with the heavier tasks such as mooring ashore in the middle of winter, serving the older crew, and doing longer shifts. Then there were a couple of murè , cabin boys aged 7–15, who had to learn the trade and performed the most menial jobs, such as preparing and cleaning the fucone (brazier), sluicing the deck and removing water from the hold.

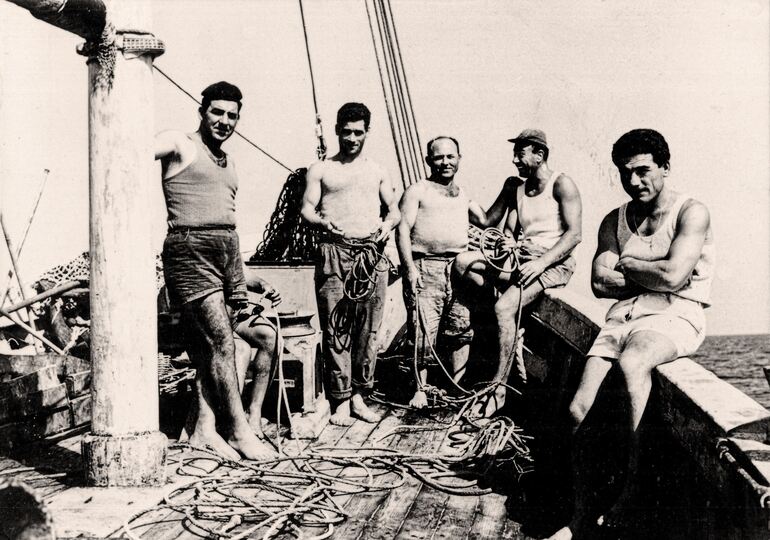

The crew on the larger vessels that were more common until the outbreak of war in 1915, consisted of around 10 people organized in a severe hierarchy. The parone was the skipper – sometimes also the owner of the boat – partnered by the sottoparone – deputy skipper of the sister vessel sailing downwind. There were about seven marenare, sailors tasked with fishing and some navigation;

This distinction of roles and their importance was reflected in the distribution of the food and the catch, which was divided into parts: the parone and sottoparone (skiller and deputy skipper) received a part and a half and a part and a quarter; the sailors a part; and the murè from a quarter to three quarters depending on length of service. Lu sbalzocche (or sbarzocche), the labourer responsible for unloading the fish and preparing it for the market was also given part of the catch.

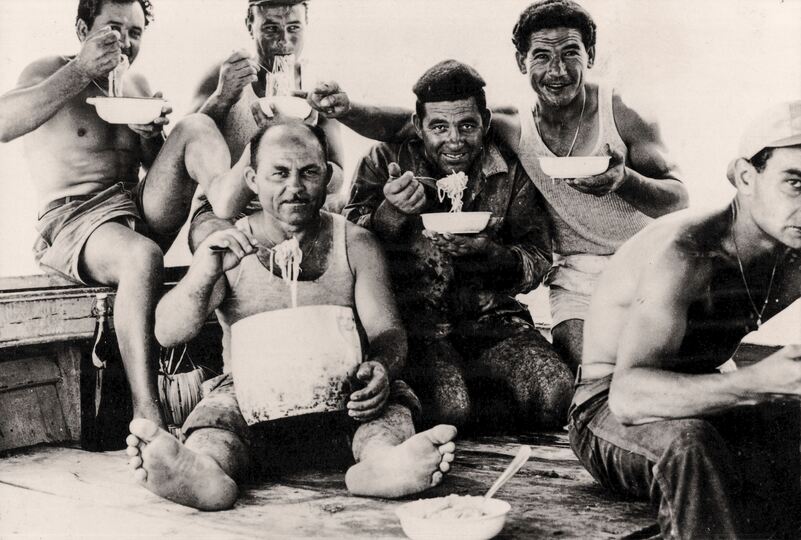

There, still naked, the giovane quickly had to climb up the topmast to unbend the sail, while the sailors hoisted the bow anchor weighing 50kg on board and the parone took the helm. Around ten in the morning, with the fish caught during the first haul, the sailors prepared their brodetto – seafood soup – in an earthenware pan but if the sea was rough, the fish was roasted with skewers stuck into the brazier sand. When the soup was ready, everyone squatted in a circle around the pan of broth with a slice of bread to use as a trencher. The sauce was poured into a terracotta pan to wet the bread then the skipper touched the deck with his right hand, kissed his fingers and uttered ”JasùCrist!” – Jesus Christ in dialect – in thanks. The parone was the first to soak the bread and take the fish with the tip of the knife and each sailor could consume only the fish he found in front of him in the pan. During the meal, wine or water and wine was drunk, while to quench thirst during the day, so as not to consume too much of supplies, a small quantity of vinegar was added to the water and a buvanda (drink) was made.

Life on board the paranza was very hard, especially for the boys. The trawl boat set out to sea at night and the giovane – a young sailor – who slept on board had to be woken up to get the fishermen onto the paranza. Even in winter, the giovane would roll his homemade wool sweater up from his chest, take off his salpatùre or salvarelle (knee-length shorts) and go naked into the water. On the beach he loaded the sailors on his back and took them aboard. Then he went back into the water to retrieve the two four-arm killocks buried on the – after having dug out these 25kg anchors, he would load them on his back and carry them on board ship.

When the weather was good there was always plenty to do from one casting to the next: the various ropes (cummanne ) were made, sails were patched or the reefs were strengthened if the wind increased, while every two hours the muré had to drain the water penetrating the hull, which was not always perfectly waterproof.The fishermen wore the very simple clothing described previously and in addition to heavy sweaters and sheep’s wool long johns, they wore an oilskin, also made at home on the cotton and linen loom, sewn in the shape of a hooded shirt. To make it waterproof the women brushed it with raw linseed oil and left it to dry in the sun. On the boat it was normal to go barefoot.

at the end of this process, the skipper took from the pile of best fish a part intended for his own needs. Only the most skilled would receive a small sum of money as a reward. Upon the return of the paranze or battelli to sore, the fishermen’s wives went down to the shore and collected their panire, a truncated cone-shaped rush basket containing the family’s share of the catch, some of which could be sold.

The Abruzzo paranza stayed at sea for long periods of time – two or three weeks. In this case the boat owner and his sbalzocche would sail out on a battello of about 7 metres as far as the fishing area to track down his boats, which he could spot from afar thanks to the symbols drawn on the sails, collecting the catch and delivering the mappina – a cloth filled with food prepared by the fishermen’s wives. The catch was divided on board and the best fish was sent to auction while the part of lesser quality was divided among the crew and was used to prepare the scafetta, the payment in kind to which every fisherman was entitled. The parone could remove or add fish to each fisherman’s share according to his unquestionable judgment, depending on how well or otherwise the sailor had acquitted himself during the day’s fishing;

The brodetto cooked on the paranza was made from what the wives prepared when they went home. The fishermen chose the small, less precious fish that came out of the net at the first catch: cod and poor cod, scaldfish, monkfish, gurnards or scorpion fish, dogfish, octopus, red seabream, spiny lobsters or mantis shrimps etc. and they cleaned them by washing them well with sea water. In the meantime, someone would light a coal fire and place the pan for the soffritto on it, with olive oil, two cloves of garlic and four or five dried peppers (li fiffillune), which were fried over a low heat (in the absence of oil, caught cod livers were used). As soon as they were browned, the peppers were removed and left to cool before being ground in a mortar with coarse salt. Immediately afterwards a glass of wine vinegar was poured into the pan and then the fiffillune. As soon as the sauce began to boil, the fish was added: first the octopus, then the tougher fish, followed by the others. The pan was covered and left to cook over a high heat; after about twenty minutes the brodetto was ready.

The economic situation was heading towards a slow decline and the progressive mechanization, with the introduction of paid work, began to cause the disintegration of that society built over the years with hard work and sacrifices by a group of enterprising people.

In the 1930s, fishing began to change radically with the introduction of motor boats. In Abruzzo, the change to motor propulsion system was slow, combining the first small motor fishing boats with more manageable paranzelle and lug sail boats. However, these first engines forced many fishermen into debt and were neither efficient nor suitable for towing heavy fishing nets, with boats still unsuitable for installing engines, while the smaller fishing vessels were only able to guarantee family survival.

Already in 1950, at a national level, over 60% of fishermen were employees, meaning that fishing, traditionally managed at family level, had transformed into an effective entrepreneurial activity. The disappearance of pre-industrial fishing systems and the consequent abandonment of social organization models on board and in costal villages, with all the positive effects on the improvement of living and working conditions but destructive effects on the fish environment caused by intensive fishing, have not, however, completely erased an identity culture that still survives and sometimes re-emerges in the history and proud stories of the ancient fishing families.

At the end of the Second World War the surviving vessels were recalled to service and many of these were empirically powered, recycling the engines of Allied tanks being demolished, eliminating yards and reducing the height of the masts. Even the heavy, fragile trawl nets were transformed, replacing the hemp with nylon, a lighter and more long-lasting synthetic material able to multiply the catch capacity and triggering a crisis in the rope-making profession. The use of old Abruzzo boats for fishing, thanks to the quality of the oak, continued until the 1960s when Italian Naval Registry engineers prohibited their use for safety reasons.

Sviluppato da Microware s.r.l.

www.microwareitalia.com